Category: Michael Wasson

REVIEW: Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

by Michael Wasson

In the body, where everything has a price,

I was a beggar. On my knees,I watched…

So begins Ocean Vuong’s frontispiece to his haunting and quietly devastating debut collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds.

It is here within the body where we begin to take in the world of this book. What really makes this entrance to the book remarkable is how Vuong’s speaker understands that the experiences we enter hold consequences. It is on the knees where we sacrifice and remain obedient to our senses. And it is the eye through which we witness the chaos of beauty. Vuong’s book stations us here who are—at the border of our flesh—trying to make sense of our lives.

Beginning the first section, Vuong shares with us the re-imagining and re-witnessing of poetic myth. From a snake left headless and still “in this version,” reminiscent of Milton’s Paraside Lost, to Telemachus pulling Odysseus “out / of the water” and dragging him by the hair through the crush and surf. This re-witnessing accomplishes and moves far beyond an appreciation for ancient literatures, but it gives us the opportunity to enter the myth to discover ourselves fully alive inside its narrative:

He moves like any / other fracture, revealing the briefest doors.

One of history’s most violent poems is Homer’s The Iliad. But what Night Sky with Exit Wounds introduces to us in “Trojan” is the idea of the body as the Trojan Horse—the strategic event between The Iliad and The Odyssey. The body is human-built. The body carries our “brutes” and war-sharpened “blades.” It holds our own people craving to return to their families and homelands. It even reminds us of our animal-likeness. But on a human level, it is the physical body we see when violence is enacted, or—as Vuong puts it so powerfully—“when the city burns.”

Night Sky with Exit Wounds grounds itself, too, in the American self, the American body, as a product of war. Here, insisted toward the end of “Self-Portrait as Exit Wounds” and the ending poem to the collection’s first section:

Yes—let me believe I was born

to cock back this rifle, smooth & slick, like a trueCharlie, like the footsteps of ghosts misted through rain

as I lower myself between the sights—& praythat nothing moves.

What strikes me is the poem’s ability to “let” the “deathbeam” continue to pierce these different scenes inside the realm of a country amid violence. I find that even against a force of death, against all these different instances of terror, it is the speaker who argues to just let it happen. Why? Because the exit wound is the self. The exit wound is the speaker’s ability to move into and through the world. The exit wound now kneels down, praying for stillness to begin its process of healing.

Reading through the book countless times, even starting from the last poem to the first, I realize more and more just how powerful Vuong’s ability with form is. From longer poems to short couplets, gorgeously scattered lines broken and strewn over pages, to anaphora and prose breaks—the single poem that most entered me and stayed was “Seventh Circle of Earth”—with its title based on Dante’s seventh circle of Hell where the innermost of the three violent rings is made of burning sand and rain, meant to encase sodomites and blasphemers in flames.

But again, it was the form that forced me to look “into” and “away” from the mostly blank (or in this case, burned) pages. All that we see in the major white space—headed with the Dallas Voice epigraph about a gay couple, Michael Humphrey and Clayton Capshaw, murdered by immolation—are numbered footnotes, seemingly markers that are to guide us to the lines recorded at the bottom of the page. Vuong has single-handedly and via the labor of lyric forced us to stare into the white ash of immolation. So by replicating that “look into the wreckage yet we look away” urgency, we are then made to hear the voices of these lovers.

4. … Speak—/ until your voice is nothing / but the crackle / of charred

5. bones.

Toward the end of Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Vuong includes this devastatingly tender and gracious poem first published at The New Yorker that echoes not simply Frank O’Hara and Roger Reeves, but the role of lullaby—the role of song and lyric to comfort us, even in the face of the world’s terrors:

Don’t be afraid, the gunfire

is only the sound of people

trying to live a little longer

& failing. Ocean. Ocean—

get up. The most beautiful part of your body

is where it’s headed. & remember,

loneliness is still time spent

with the world.

Ocean mentions in an interview with David Winter that this poem is his way to “speak to my own shadow,” and what better way to comfort than to know that our own darkness, too, is listening and living there breathing beside us.

Many of us were beyond thrilled when Copper Canyon announced that they would be publishing Ocean Vuong’s first full book. Many of us had one (or both) of his chapbooks (if they weren’t sold out at the time) and read his poems as they entered the world. Many of us were changed by encountering his work—like beautiful literature should. How it challenges us to enter a space and be transformed by language.

And many of us I’m sure learned from how his speakers paid homage to the beauty inside the crush that his words seem to do so gently. So where do we stand after entering and departing Night Sky with Exit Wounds? We stand without a doubt—as the world continues to move under our feet—in awe of this brilliant and humble talent gifted to American poetry.

I am thankful having his book with me. Its pages continuing to remind me, “are you listening?” I am.

Buy it from Copper Canyon Press: $16.00.

Michael Wasson is the author of This American Ghost (YesYes Books, 2017), recipient of the Vinyl 45 Chapbook Prize. He is nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation and lives abroad.

REVIEW: LETTERRS by Orlando White

by Michael Wasson

“It begins at a diacritical spark… of breath… and soma”

And so we enter Orlando White’s meditative, intelligent, and echoing second book, LETTERRS, both a collection of unsettling silence and precise clangor. As a shift from his first book, Bone Light (Red Hen Press, 2009), White moves from the examination of thought to the philosophical relationship between print and sound.

Within the utterance and inscription of a letter, LETTERRS advances what a poem does in its own tightening—that is, how a poem resists, subverts, and fragments so-called tradition. We begin with “Nascent,” a long poem playing out a woven origin between sound and flesh.

White possesses an incredible, deft hand in setting a word with amplified effect. We find ourselves in the clocklike uterus of the poem’s process—a slowed down act of creation. At each break, at each movement of language, we throb into rhythm, weighted, layered, wrapped in meanings that propagates at a velocity maintained by the page. His opening poem carves out a trajectory like a wavelet of sound escaping the lips and pervading the air.

As such, White very much considers a poem’s “air” space—how effect travels and is guided by the simple act of a person reading his “letters”—and he does so via the tension of uncolored emptiness fielded between each word; the human, bodied shapes communicated among letters, sound, and thought; and through the many depths of meanings that words carry along with them from the past and into the present. For instance, his “Nascent” uses the word ictus: a rhythmical or metrical stress, or a seizure/stroke.

We are given the graceful tempo within prosody, and yet we hold the medical meaning of a seizure—a violence stripping the body of its control.

If we read the white spaces with as much care as his use of word meanings, we will begin to see the poems in LETTERRS methodically blooming, firing, fading, quivering, and breathing—all so gradually. In the midst of a single word, even in the process of a poem unfolding, White submerges us into the body of the page as it undergoes its powerful gestation, echoing his words as though their very ink carries the weight of myths, creations, stories, truths, and sound from the inside of one’s own body to the light of the living world.

And once we are spoken, possibly in one’s mother tongue (here at times Diné bizaad, which is beautifully woven in), we undulate our very existence out to one another. White provides some philosophical puzzles that help lay out a clearing into which we can reach: Are we indefinite? If so, and if our languages, either written or oral, strive to live in perpetuity, what happens when we are silenced of our language? How do we interact with our languages?

Through a large portion of LETTERRS, we are seated to watch the stories of alphabetical letters develop. White’s speakers ask us to participate in each letter-headed poem—from a to o. We see an a as an ox, telling us “People create from what their objects / create for them.” answering immediately, “That’s why text behaves,” why text is a living entity.

Likewise, the speakers of these pieces are not so much prophets or philosophers as actual truth tellers, examining how space, ink, gesture, stroke, and being are commingled together to create our orthographical perceptions. We hear d gasping nearer to our eardrums; we sound out like kids again an e, us and the letter both genuflected “to worship in silence”; g is curvilinear shaped like the innermost bone-work of a human ear, asking “how does a letter become another when its origin / is lost? n begs us to consider our very own being as it swings between “page, ink.”; o is an eye, an aperture, funneling our vision as the nerves constantly diagram light, white, dark, and depth.

Masterfully, White holds us in light of his book’s arc, which started at the beginning, before the very first words of “Nascent,” á la Edwin Torres: “Poets are citizens of language.” We are to live inside language, deep beneath the flesh, embedded like bones, hearing and sounding out—erring along the way. But, as such, we too are language citizens, part of a larger narrative and aggregate that practices language to continue its mysteries, failures, flaws, and successes.

I think from “Nascent” to “Unwritten” to “Finis” and “Cephalic,” White opens us up to an echoed landscape in which letters, writing, sound, and thought slow down to eye one another closely. So close you can hear their eyes blinking. White engraves his poetry into us to reveal the shapes of our letters like “a limb still composing,” something stretched around us like skin, “always tightening.”

And just as we take pen to paper, it is White who reminds us to participate. To “behead the i, and watch its dot head roll to the back of a sentence.”

A powerfully intelligent book by an indigenous writer expertly capable of writing the procedures of our own human acts of communication—these fleshed and sounded letters.

Buy it from Nightboat Books: $17.95

Michael Wasson earned his MFA from Oregon State University. He is nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation and lives in rural Japan.

REVIEW: Storm Toward Morning by Malachi Black

by Michael Wasson

How might we find ourselves filling the vacancies in the small pieces of the world around us? How might this feel when we know that the psyche we carry along is central to our suffering? In his debut book of poetry, Storm Toward Morning, Malachi Black is not so much our complete answer to these questions but an attempt to beautifully transcribe the experience of questioning via meditative exploration.

Take for example “Psalm: Pater Noster”:

I am your plum:

Enfold me

in the shadow of your mouth

and I will echo as a taste

against your tongue:

I am

your praise:

To search out the world for metaphors and adding meaning to our experience is a central concern for these poems, and we find ourselves participating. The speaker informs us that it is our plum. Adding urgency and palpability, Black’s speaker seems to be desperate in fixing us together. We are devouring the plum. Hungered. It echoes across our tongues. We praise it.

Here, too, the speaker mines into us. At the same time, we want it. In time, through the pulse of the poem, Black’s speaker has become a part of us. Desire. The need to be wanted. That satisfaction, the very suffering of loneliness reaches out and slips in, transforming from the ache of the mind to the fleshy plum opening in your mouth. And the best part is that you, yes, want it.

Religion and ancient literature seem to ground the collection well. Not oversaturated, but briefly, effectively so. In the aforementioned poem, I notice at first it’s headed with “The Lord’s Prayer.” Throughout, but not limited to, Black helps us reenter Dante’s Canto XIII—the suicide woods—; we witness the canonical hours that he notes is a condensing of “the traditional quarantine period of forty days and forty nights into the passage of one day”; and we see gestures toward Caesar, Archimedes, Marcus Aurelius.

What I find with Black’s clear-eyed and intellectual use of these figures is a profound sense of inwardness by looking to others. Again, it’s that way of locating pieces of the world—be that literary events or a baby grand piano—that we can fill in with ourselves. With Dante’s Canto XIII, Malachi is attentive to the tree in agony: “The tree can speak, and it will shriek until a whole head hangs by a neck-like stem with a dumb body dangling beneath. And hell has won: once borne, the body drops. Another one’s begun.” How much like lives in cycle Malachi Black showcases with this grim scene.

How much like being born, like suffering and hanging on to life, and finally in an instant like dying and being reborn again we simply are in our experience.

Storm Toward Morning is one of those true to form, true to innovation and to ancient concerns of humanity—which seems to always be reoccurring in some way or another—and true to the music in our questioning. We feel guilty in defying powers around us. We feel relieved to break bonds. We are anguished. We are joyous in our celebrations. And we are carving the outlines of our consciousness in the world around us. Malachi Black takes us closer to ourselves and illuminates how “… to burn on.”

A genuine, masterfully skilled, and powerful debut in American poetry—haunting, reflective, and guiding us through by its light, through the dark ruptures of our living, Storm Toward Morning is a magnificent book.

Storm Toward Morning is available from Copper Canyon Press.

Michael Wasson, nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho, earned his MFA from Oregon State University and his BA from Lewis-Clark State College. He received a Joyce Carol Oates Award in Poetry, and his work is included or forthcoming in Poetry Kanto, As/Us, Hayden’s Ferry Review, American Indian Culture and Research Journal, Cutthroat, and elsewhere.

REVIEW: Souvankham Thammavongsa’s Light

by Michael Wasson

Can it look so effortless to locate us in a bright opening as Souvankham Thammavongsa’s book Light? Her collection begins, “This is a clearing,” a spatial entrance so cleared of everything but one caveat, or “one rule,” that you “will bind to yourself like a promise / to begin.” In a way, we’re guided along and given a clear outline.

At the outset, the speaker brings us in, demonstrating how to start. With such a deft and soft hand, Thammavongsa doesn’t so much as urge as she lets us become receptacles to the possibilities of what’s before us: light, shapes, direction, and the very marked contours that remain here.

Reading Thammavongsa’s Light, we can’t help but feel opened, but not so much in a vulnerable way—as in grief or bearing fresh wounds—but merely as passive bodies left open at the lips pressed between the dark and light, the point at which a singular transformation enters us so easily. And to be transformed openly is a common concern for these poems:

fie mot is what happens when you’re not expecting it

This poem “Fie,” one of many that examines how another language says light or some sort of light source, shows us how to say fire in Lao. Going through the foundation word of fire, or fie, provides us then with how to say words for flashlight, fire when it burns through structures, or the sound of thunder. In Thammavongsa’s gentle surgery and guidance through several languages, we are in the audience role as a vessel—simply driven in place to receive, not expecting complex issues or dense manifestos.

Thammavongsa’s poetry is one leaning on the grace of simplicity, never overtly didactic, never verbose or meandering. Each poem explores our central theme: light. To be lit, to experience its absence, to need it, to part with it, to experience how slowly devoured we are by its presence, and in a way, almost speak for it.

Also, in the same vein, Thammavongsa illuminates the “marks”—I’d clarify as the “letters”—of her poems, allowing the whitespace to create clearer utterances within her poems. Her lines seem airy, almost floating. They are wrought with her initial declaration of “This is a clearing,” which we can then realign as “these are clearings,” creating a link from the book as a whole all the way down to the light pooling between her syntax. It’s a lovely, threaded effect.

Like light, Thammavongsa’s Light touches on so many aspects on a human’s life, too—failure, preparing for a return, text on the page, ceremonializing awe, love, and the beauty of continuation, as in the poem “Mountain Ash,” in which we know “Ash is what fire leaves behind” but we are challenged to consider that there is more: “Whatever we know of fire, we know it is not done.”

The most salient poem of the book, I find, is “Questions Sent to a Light Artist That Were Never Answered,” an unforgettable piece that equally critiques and advocates our obsessions:

- When you think about the word light, what comes to mind first?

- Do you work with real light (light from the sun) or only with electrical light?

- What are you trying to do with light?

- Do you think or work with the dark?

- What can’t you get light to do?

- Why light?

This book straightforwardly articulates its singular concern, thereby letting its source to permeate from the speaker’s vantage point. Again, we remain open, we are accepting, and ultimately we are changed in the process.

And in all its observations from a giant squid’s eye (that could absorb so much light but why so when it lived “where there was no light at all”) to the refracted, anaphoric effect of constant memories of one’s life surfacing, Light is a rich, enlightening experience that honors human curiosity. It’s a journey that I’m delighted to have embarked on with such a clear-eyed guide as Souvankham Thammavongsa.

Light is available from Pedlar Press

Michael Wasson, nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho, earned his MFA from Oregon State University and his BA from Lewis-Clark State College. He received a Joyce Carol Oates Award in Poetry, and his work is included or forthcoming in Poetry Kanto, As/Us, Hayden’s Ferry Review, American Indian Culture and Research Journal, Cutthroat, and elsewhere.

REVIEW: Ozalid by Biswamit Dwibedy

By Michael Wasson

Linguistic torsion. There’s really no other way to put it.

Before I had even started reading Biswamit Dwibedy’s compelling debut, Ozalid, I flipped to the back of the book for the blurbs. Cole Swenson mentions, “we’re in unmapped territory.” Immediately, Ozalid had offered some form of curiosity to me, spurring me on to take a dip in its depths.

Let’s begin, though, at the title: Ozalid—a process in which type and graphics are duplicated onto translucent paper. When I was slated to review this book, the name itself had already drawn a simultaneous confusion and a fascinating intelligence.

The poems throughout seem to meet at a plane of space where language, at its core, is found at the time it recedes away. In doing so, Dwibedy’s poems flicker, flutter, dissolve, and interact with its almost bizarre language placement. The rippling white space therefore really shapes the book’s flow.

The poem “Vein,” for example, depicts what could be a human vein “[a]slant / against its / own / defined on / soft mud.” I’m thrown off, expecting to follow the path of the vein against its own. It’s own what? As readers, we’re dissembled right then and are pivoted into “defined on / soft mud.” The logic of the syntax and rhythm is torqued just enough that we’re redirected with the image of the vein still somewhere in our peripheral.

gathering

enough that perfect rain –

behind

that mud

finally

equals

footsteps

In the same poem, after our redirection, we can follow along like a lens that has found its focus. We see the development of footprints, equality, balance, a sort of superimposed image that has discovered signs of human remnants beneath its initial surface texture.

I think what Dwibedy has touched on is an intimate relationship with the strangeness of language and letters. Having touched at these accounts of language’s ever-present ephemerality, Dwibedy comes to terms as best he can:

The beauty of letters

to tremble

& then

to come

to know them

in sequence

love ends badly

In the middle of this poem, “Barely Touched,” the speaker says, “Anything could happen.” How precise. Anything can happen when dealing with creation and art-making. That’s the failure inherent in process. At all times, in life, in human wonder, we’re woven into a world of the living and dying—the dead and the newly born. So this is how that line haunts—because then at large Dwibedy is conscious to the bright, aperture-quick stains of suffering, of failure, of success weighed down by its uncertainty, its “unmapped territory” as Swenson fittingly gathered.

But also then the collection is a testament to how art is a process toward powerful discovery.

At the gut of this collection, however, there is always an air of mourning, and it’s not really until you slow down and hear the heartbreak within the speaker. Like the aesthetics of impermanence, Dwibedy’s takes on an impossibility, an almost but not quite, an attempt to pin down shadows in the harsh surge of light, only to see his poems’ experiences, and his readers’ as well, drenched in awe and grief.

Dwibedy offers us “Which the mind is a chain of pauses” at the end of Ozalid, almost as a way to reaffirm our entire course through the book. And even though this is expressive enough to sew us down, the final line of the collection mirrors my conclusive sentiment: “amazed across the way.”

Michael Wasson, nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho, earned his MFA from Oregon State University and his BA from Lewis-Clark State College. He received a Joyce Carol Oates Award in Poetry, and his work is included or forthcoming in Poetry Kanto, As/Us, Hayden’s Ferry Review, American Indian Culture and Research Journal, Cutthroat, and elsewhere.

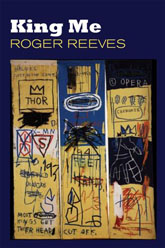

REVIEW: King Me by Roger Reeves

by Michael Wasson

This is America speaking in translation, in glitter,

in gold grills and fried chicken. Auto-tune this if you must.

Roger Reeves’ debut collection, King Me, marks an impressive, I would even say needed, contribution to contemporary American poetry. His poems here present an America that is personal in its specificity, myriad in expanse and scope. Reeves’ hands and mouth drip with the intimate relationship of beauty and violence.

The lyric in his book confronts us—chapped, curled sores, delicate to the touch, its bright wounds scattered as pleasantly as autumn clovers. His opening poem, “Pledge,” is a stark reminder: leave every painful, lovely, and often ordinary experience behind. Leave a wake of presence. In it, Reeves’ crafts negation, imprinting a slowly developing absence. Remaining for us:

I leave, I leave—this will surely leave a stain.

King Me ceremonializes historical and social uses of language, too. In “Cross Country,” which I first quoted at the beginning of this review, we are witness to a speaker teasing out both creation and undoing of the black body, an American corporeality:

Here,

below this golden altar, the making and unmaking

of my body.

Reeves strains, croons, unmistakably finding refuge in the service of honoring a life and well as a death. It’s almost too much to handle, but Reeves guides us with as much of his grace as his muscled encouragement. His hands hold onto a lush sprawl of experience that moves from “the blue / hour of a field” to “the bog at the end of this road” to “a city that is running out of water.” History moves. It casts its line from the past to the very modern glitz of an urban space drying out, pocked and tattered, streetlit and concrete. And still Reeves sings out to us:

Pulling pulling, pulling. Think: nigger is the god

of our brief salvation. Nigger in a body falling toward a horizon.

And for the poet to keep hauling, to wrestle with language, it’s the repetition of his lines that provides us the energy deep from within his tongue. He reminds himself of the fiery convulsions that lie beneath the calls and responses to racial slurs. He gets as close as he can in understanding the emotional depth of this language, almost similar to how Yusef Komunyakaa articulates “Facing It,” to say “I’m flesh,” I’m human, I’m placed inside the skin of the memorial of history, of language, and of the self—full body mirrors shimmering at every angle.

This book is also “[o]pen as a wound,” showcasing a dual reality between healing and its stinging lesion.

I belong to the silence of a pomegranate

just cut open, the red seeds

pebbling a white plate.

Here, “Of Genocide, or Merely Sound” illustrates an afterimage of that opened wound, and Reeves locates his readers into that sound, building dissonant tension into the initial beauty of fruit. As those seeds rest on the plate, we sit patiently to pinch the seeds to our tongues.

Another perspective, too, Reeves does a masterful job at intersecting the reflection of the contemporary self with figures from the past. In a way then these poems investigate both damage and resilience embraced at a middle ground—a constant threading of historical fabric to our present modernity. And he’s not afraid to include the perforations and sewn lines that needle pins leave behind.

Throughout, self-portraits help to structure King Me. We hear Tiny Davis, jazz trumpeter and singer, Duchenne, French Neurologist, Van Gogh, and even Love in Mississippi. King Me is just that. Holding the ancient crown, those who’ve honoring the past—an entire lineage of people, bodies, deaths, and reputations—and wearing it today, singing of all the aligned human flesh.

Reading Reeves’ collection will give off multitudes of emotion. Several sensations at once. The slick wet tongue on dust. The dry hands parting the water. Fire drying the wet clothes of the impoverished. The horror and splendor of American identity.

This is a needed book.

The end insists the title “Someday I’ll love Roger Reeves.” Well, Roger Reeves, someday seems more like every day—or every poem that fleshes out the texture of this book.

Can I say it again? King Me is a needed book.

King Me is available from Copper Canyon Press

Michael Wasson, nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho, earned his MFA from Oregon State University and his BA from Lewis-Clark State College. He received a Joyce Carol Oates Award in Poetry, and his work is included or forthcoming in Poetry Kanto, As/Us, Hayden’s Ferry Review, American Indian Culture and Research Journal, Cutthroat, and elsewhere.

Poetry Is Not a Project by Dorthea Lasky

In her chapbook, Poetry Is Not a Project, Dorothea Lasky offers us insight to how poets may be going about discussing their work, or their “projects.” However, Lasky penetrates this notion by saying outright that poetry is not a project, as the title of the short electronic text clearly articulates across its cover page. And during my first read through, I ate up the pages. It is a short piece but incredibly noteworthy. Lasky covers major, theoretical, and argumentative ground in the almost 20 pages of content Poetry Is Not a Project is.

In her chapbook, Poetry Is Not a Project, Dorothea Lasky offers us insight to how poets may be going about discussing their work, or their “projects.” However, Lasky penetrates this notion by saying outright that poetry is not a project, as the title of the short electronic text clearly articulates across its cover page. And during my first read through, I ate up the pages. It is a short piece but incredibly noteworthy. Lasky covers major, theoretical, and argumentative ground in the almost 20 pages of content Poetry Is Not a Project is.

Lasky, both effectively luminous in her polemic, essayistic prose and ambitious in her art-should-be-art idea, organizes her argument into four sections: Habitus, An Example, What is Really Not Intention, & What We Write And What We Write for.

Each micro-chapter tightens what Lasky contends as a failure to understand what poems and projects imply. Art making is the blood and muck of single utterances that investigate the human drama of our universal consciousness. That poems dig into this drama and make their hard-earned message available to our humanity is a dark path. A project then, according to Lasky, illuminates that darkness. It holds too much certainty. It fashions an overwrought, future-oriented destination of art. She proclaims, “I want this century to be full of poets who write poems, not full of poets who conduct projects and nothing more.” And Lasky handholds us. Gives us reason to ruminate. Why settle for mediocrity of poem-making for hip ideas meant for a portfolio?

Each poem should be its own endeavor in the mysteries of itself. Lasky urges poets to discover the nonlinearity of their journeys. The twists and turns. The moonless nights. The sudden joys and sufferings and rich human stories embedded beneath the meanings that poems birth. Don’t name your destination. Don’t settle.

Naming your intentions is great for some things, but not for poetry.

Along the same lines, Lasky illustrates that understanding all the meanings and goals of a poem you plan to write is folly. It suffocates any possible discovery. It suppresses what you might find deeper in the poem’s world. You have only a concept. An idea. An empty space with clean corners—lacking the extravagance and boldness in risking yourself for the poem.

Any other way, all you have created is just a decorated empty room.

Though poets like their whitespace, Lasky advocates for a dark space, an uncertainty to the poet’s line of vision. As poets shift to think more kaleidoscopically, they face the blood and organs of experience—the breath and warmth—of adding air and energy to the empty room. She fills it with content. Not just the skin and bones. Not just the single musical note but a bended note that tells a story, colors with sustain, and curves with gut-wrenching intensity. No illuminated maps to see our way through the poem. No last lines that show us where to go.

The terrain of a poem is unmapped.

Lasky divulges a truth we need to consider. She tells poets to start “valuing poems over projects” because a project tries too hard to name or taxonomize where its destination is. It projects light in a single straight line, when what poets should really be doing is scattering the light, mixing it up with the dark heft of their struggle to shovel deep into the earth. Poets should scrape at uncertainty and should celebrate their discovery of poems, of art-making—rather than glaze it over with intention.

Ultimately, in her brilliant, oh-so-Lasky-way, she calls on, “let’s make a party, poets. And let’s have everyone join us there.”

Yes, a party for the ages where Lasky’s encouragement may as well be the savior from our rhetorical mediocrity. In all seriousness.

Her chapbook is powerful. It reminds us that poetry isn’t a project. That poetry is the disordered havoc from which we gain clarity and insight. That poetry is hungry. It is survival in the dimmest of places.

Lasky lays her earned claim, her graceful yawp over not just the great American poem and its poets but over poetry that stretches across the rooftops of the world, “I don’t think Emily Dickinson gave a damn about a project.”

We would agree. I mean, what is a life without surprises deep in such promising mystery?

Poetry Is Not a Project is available for free from Ugly Duckling Presse

Michael Wasson, nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho, earned his MFA from Oregon State University and his BA from Lewis-Clark State College. He received a Joyce Carol Oates Award in Poetry, and his work is included or forthcoming in Poetry Kanto, As/Us, Hayden’s Ferry Review, American Indian Culture and Research Journal, Cutthroat, and elsewhere.

When My Brother Was an Aztec by Natalie Diaz

When My Brother Was an Aztec / he lived in our basement and sacrificed my parents / every morning.

So goes the frontispiece of Natalie Diaz’s poetic debut, When My Brother Was an Aztec. This title, which the start of the poem weaves in, suggests a character adorned in regalia, surrounded by a landscape of cultural violence and astonishing beauty. It braids together myth and ancestry with the speaker’s own familial blood, the brother.

We are witness to sacrifice, and Diaz gives us hard truth, holding to our faces legless, armless torn bodies of parents beaten and defenseless. How an opening poem can resonate and launch its reader’s into the book, When My Brother Was an Aztec hurls us on a trajectory that splashes open a bodily wound somehow either personal to our lives or extravagantly powerful in showing outsiders this hellish vision, this Aztec.

Yet like the neighbors who were “amazed [the] parents’ hearts kept / growing back,” I find a truth, a human throb to love a son struggling with addiction and terror that comes from a life on the rez, a life clanged together from the harsh world some of us are subject to.

Entering the book thereafter, Diaz strikes this warning, this reality: “Angels don’t come to the reservation.”

This book is muscular in being direct, outright in its establishment of landscape. This poem, “Abecedarian Requiring Further Examination of Anglikan Seraphym Subjugation of a Wild Indian Rezervation” situates a context that will thread throughout the book. The landscape is made up of all sorts of characters, items, and tensions between mythic struggle and an observer who is simply a part of it all. We see, among other pieces that build this world, pinto beans, raisins, a rusted bus abandoned in the Grand Canyon, an ambulance driven by Custer, stiletto moccasins, a copy of Indian Country Today, WIC Coupons, Ataris, gutted lightbulbs, locusts, commods with that bold black lettering, and a grandmother’s missing legs.

Diaz doesn’t stop there either. Her hand at narrative is also character-driven. Such appearances by Guy No-Horse, Jeremiah, blonde tourists, Mary, Betsy Ross, tribal dentists, Eve Side-Stealer and Mary Busted-Chest (asking “What if Eve was an Indian”), Jimmy Eagle, Jimi Hendrix, Lionel Richie, and even Antigone and a Mojave Barbie all help to provide a dimension of people that illustrates the subjugation and tragedies inherent in humanity.

So rather than gesturing with lush insights and poetic epiphanies of often-overwrought opulence, what this book does best is explore its severity to unearth such grace the reservation hides beneath its flesh. It also carries with its unfolding an ache:

When we leave, our hunger will go with us

In truth, each character and moment of brutal exactness, each important object etched into these pages possesses a hunger—an absence wanting to be filled. Yet no matter how empty the bellies are, no matter how “shame-hollowed” these songs are, they express growth and resilience, as a book of poems should. Poems collected, like these, attempt to stay alive.

The arc, then, demonstrates a process of resilience. The book moves in the first section through childhood, puberty, adolescence, an awareness to tribal and cultural history, and an underlying shame; into witnessing a family torn apart, watching the brother as he “tears the temple to pieces” (“Formication”), and feeling the grief and ruin left of a family affected by relentless addiction; and finally toward desire, the body, satiation, politics, war, wounds, love, and healing.

Diaz makes the moves necessary to prove that survival is the center to her world, the core of this narrative development. These poems need to face terrible truths. The poems demand a toughness from both the poem and the reader. At the heart of resilience is the ability to witness, move forward, and reflect. Here, in the poem “My Brother at 3 A.M.,” we are reminded of that frontispiece, the Aztec vision of sibling in a restless state of instability. Interestingly, this too translates to the speaker and ultimately to us. To see the brother sitting on the porch at 3 o’clock in the morning, the speaker records:

He sat cross-legged, weeping on the steps

when mom unlocked and opened the front door.

O God, he said. O God

He wants to kill me, Mom.

As this poem, a pantoum, unravels, it inverts the feeling and dialogue of the brother and mother:

O God, see the tail, he said. Look at the goddamned tail.

He sat cross-legged, weeping on the front steps.

Mom finally saw it, a hellish vision, my brother.

O God, O God, she said.

Moving through, the end registers a woven beauty to When My Brother Was an Aztec, which I cannot help but feel a personal timbre with. The reservation. The ferocious addictions. The cracked landscape that houses in its wrestled heart a buried blessing. A buried blessing that requires a moving around of the shards and heavy chunks to see. In “The Beauty of a Busted Fruit,” its speaker—amid the pain of remembering amputated legs, scars, the easiness of the body splitting apart, and the reality of slithering snake hallucinations across the skin—articulates all of this world, in all of its singing and howling, as a fondness:

…carrying your hurts

like two cracked pomegranates, because you haven’t learned

to see the beauty of a busted fruit, the bright stain it will leave

on your lips, the way it will make people want to kiss you.

Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec reminds us that the ugliness of our lives shelters how we may blossom the broken pieces to a worn yet beautiful temple. Diaz tells us over and over again that beyond the surface of the reservation rests the brightness of all that weight pressing back at us. This book moves beyond grief toward a self learning to heal, learning to devour its life, as a way to find what’s always been hidden there in plain sight, even in the knotted face of terrible tragedy. An almost unbearable grace.

Michael Wasson is nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho. He earned a Cutthroat Discovery Poet award and was a Joy Harjo Prize finalist. His work is included or forthcoming in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Weave Magazine, American Indian Culture and Research Journal, As/Us, and Tupelo Press, among others. He’s an MFA poetry candidate at Oregon State University.