REVIEW: LETTERRS by Orlando White

by Michael Wasson

“It begins at a diacritical spark… of breath… and soma”

And so we enter Orlando White’s meditative, intelligent, and echoing second book, LETTERRS, both a collection of unsettling silence and precise clangor. As a shift from his first book, Bone Light (Red Hen Press, 2009), White moves from the examination of thought to the philosophical relationship between print and sound.

Within the utterance and inscription of a letter, LETTERRS advances what a poem does in its own tightening—that is, how a poem resists, subverts, and fragments so-called tradition. We begin with “Nascent,” a long poem playing out a woven origin between sound and flesh.

White possesses an incredible, deft hand in setting a word with amplified effect. We find ourselves in the clocklike uterus of the poem’s process—a slowed down act of creation. At each break, at each movement of language, we throb into rhythm, weighted, layered, wrapped in meanings that propagates at a velocity maintained by the page. His opening poem carves out a trajectory like a wavelet of sound escaping the lips and pervading the air.

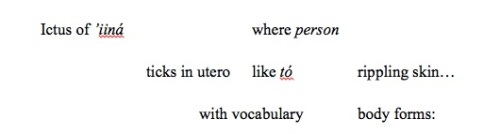

As such, White very much considers a poem’s “air” space—how effect travels and is guided by the simple act of a person reading his “letters”—and he does so via the tension of uncolored emptiness fielded between each word; the human, bodied shapes communicated among letters, sound, and thought; and through the many depths of meanings that words carry along with them from the past and into the present. For instance, his “Nascent” uses the word ictus: a rhythmical or metrical stress, or a seizure/stroke.

We are given the graceful tempo within prosody, and yet we hold the medical meaning of a seizure—a violence stripping the body of its control.

If we read the white spaces with as much care as his use of word meanings, we will begin to see the poems in LETTERRS methodically blooming, firing, fading, quivering, and breathing—all so gradually. In the midst of a single word, even in the process of a poem unfolding, White submerges us into the body of the page as it undergoes its powerful gestation, echoing his words as though their very ink carries the weight of myths, creations, stories, truths, and sound from the inside of one’s own body to the light of the living world.

And once we are spoken, possibly in one’s mother tongue (here at times Diné bizaad, which is beautifully woven in), we undulate our very existence out to one another. White provides some philosophical puzzles that help lay out a clearing into which we can reach: Are we indefinite? If so, and if our languages, either written or oral, strive to live in perpetuity, what happens when we are silenced of our language? How do we interact with our languages?

Through a large portion of LETTERRS, we are seated to watch the stories of alphabetical letters develop. White’s speakers ask us to participate in each letter-headed poem—from a to o. We see an a as an ox, telling us “People create from what their objects / create for them.” answering immediately, “That’s why text behaves,” why text is a living entity.

Likewise, the speakers of these pieces are not so much prophets or philosophers as actual truth tellers, examining how space, ink, gesture, stroke, and being are commingled together to create our orthographical perceptions. We hear d gasping nearer to our eardrums; we sound out like kids again an e, us and the letter both genuflected “to worship in silence”; g is curvilinear shaped like the innermost bone-work of a human ear, asking “how does a letter become another when its origin / is lost? n begs us to consider our very own being as it swings between “page, ink.”; o is an eye, an aperture, funneling our vision as the nerves constantly diagram light, white, dark, and depth.

Masterfully, White holds us in light of his book’s arc, which started at the beginning, before the very first words of “Nascent,” á la Edwin Torres: “Poets are citizens of language.” We are to live inside language, deep beneath the flesh, embedded like bones, hearing and sounding out—erring along the way. But, as such, we too are language citizens, part of a larger narrative and aggregate that practices language to continue its mysteries, failures, flaws, and successes.

I think from “Nascent” to “Unwritten” to “Finis” and “Cephalic,” White opens us up to an echoed landscape in which letters, writing, sound, and thought slow down to eye one another closely. So close you can hear their eyes blinking. White engraves his poetry into us to reveal the shapes of our letters like “a limb still composing,” something stretched around us like skin, “always tightening.”

And just as we take pen to paper, it is White who reminds us to participate. To “behead the i, and watch its dot head roll to the back of a sentence.”

A powerfully intelligent book by an indigenous writer expertly capable of writing the procedures of our own human acts of communication—these fleshed and sounded letters.

Buy it from Nightboat Books: $17.95

Michael Wasson earned his MFA from Oregon State University. He is nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation and lives in rural Japan.