Category: Jennifer Fossenbell

REVIEW: My Not-My Soldier by Jennifer MacKenzie

by Jen Fossenbell

Because My Not-My Soldier makes such an intricate project of honest disclosure, I would like to disclose something from the start: my reading of Jennifer MacKenzie’s first full-length collection comes from a personal deficit of relevant historic knowledge. So, despite what some people say, I read with Google handy, because I hate missing out. I’m embarrassed to admit what I don’t already know about Syria. But if I begin to get a creeping feeling that I’m one of the “too many” described in “You Are Not a Bird” who “write in notebooks” and are “lively and stupid,” I’m missing the point. These poems remind us that our understanding is always incomplete, always imperfect, always other, no matter how much we know or think we know of particularities of places and histories. The challenge posed by MacKenzie is to own up to these limitations of empathy while continuing to open ourselves up to perception of a reality that “flows into all the spaces, how / strangers test our pity.”

The indifference of “What happens on the moon is none of my business” breeds helplessness; yet My Not-My Soldier grinds away at the very notion, even when some moments and voices admit to what feels like futility… of feeling, of loving, in the face of war and trauma. “Is it tiring // to be weightless? Try helpless.”

Structurally, as well as linguistically and thematically, MacKenzie demands tenacious effort of her readers, straining to grasp what can’t be grasped, as well as what can. In this way, reader and speaker together reenact internal and physical processes of foreignization, mis– and/or re-education, displacement, and (erotic) encounter.

In a useful and enlightening conversation with Joe Milazzo, MacKenzie emphasized that the perspective of the book is fundamentally Orientalist, or “Western-eyed.” Her assembly of allusions to Western culture, from Linnaeus and Leviathan to James Blunt and Odysseus, place potentially “foreign” sensory information and events in Damascus and elsewhere in the Near East into a schema a Westerner can relate to. But she’s transparent about her orientation because one of her projects here is, to risk using an overly corporatized word, accountability. MacKenzie’s speaker strives to hold her ego– and ethno–centrism accountable—to disclose her ambivalence toward a privileged distance (even in close proximity) from the violence and upheaval she documents in fragmented glimpses. She makes us uncomfortable with the “comfortable ability to ignore” what we see, often under the guise of privacy. To be without a stance is also a stance, and MacKenzie won’t let us forget that fact. Her speaker(s) often embody and/or parrot voices that represent the complexities of subjectivity and disconnection, as in “Blurbing the Reconquista,” where she confesses that “inside me // an incredible privacy still reigns” and later, “You means other / people I don’t really see.”

Her poems show us how the very act of description can become a problematic act of laying claim to others’ lives, even in an honest endeavor to bear witness. For instance, one speaker points to herself as the documenter, recording an instance of injured protesters in Syria being tortured in the hospital:

I described the body

returned from the hospital still

with two bullet holes and the new gash

opened diagonally from shoulder to hip between

Yet in an earlier poem, the entire genre of witness poetry is called into question when she asks, “I mean, what we have described, have we extorted?”

MacKenzie also revealed in her conversation with Milazzo that the concept she feels the book most vehemently opposes is aversion. Interestingly, according to Google Books’ Ngram Viewer, the word has seen a rise in English usage since roughly the 1950s. These poems chew on a strange contradiction of terms—the fact that there is as much a tendency to turn away from violence as to be drawn towards it. We both avert and advert our gaze. It’s no wonder when we consider that the root of sensational is the same as sentient. The poem “Black Mercedes Novel” is just one of many poems that encapsulates the way our ability to see, hear, and feel fuels both intellectual engagement and mindless entertainment:

…complicity in being seen, fear sucked up

silvery in the roots of spectacle

[…]

impeccable flakes of armor

certain chances & amours attend

an inevitably unstable view

of power. Polyvocal & unsure soul

perhaps a way to stave off

history?

When violence becomes spectacle, of course, then it quickly becomes commodified—“banned, obscene, immensely profitable”—yet MacKenzie’s poems are less interested in who profits and more interested in the fact that people are willing to pay for the products of violence. A voice in the market asks, in “Small White Bed”

…& how bout those

how many thousands dead

& how much is

this blouse, so pretty

Tragedy is converted into object:

The country came into

soldiers by the trainloads advancing

grids of fire. Later they’ll place

some kind of plaque, or altar

MacKenzie is possibly at her most cynical when dealing with these ideas, and while I was initially tempted to find this cynicism a weak point in a book that seems to argue for the potential of real transformation and healing, I realize that’s unfair. Cynicism here, as in life, feels almost an organic stage of coping with the bullshit—something to go through in order to get to the other side.

Anyone interested in language in a global sphere, in its many platforms and registers, as MacKenzie is, has to deal with sarcasm and dangerously reductive euphemism. MacKenzie draws on all of these, as well as making direct references to the “mechanism skimming language from strife”. She captures troubling usages of language by using them, slamming together poignant and flippant in short succession. In the prose poem sequence “The Dead Girl,” we find references to teaching English (MacKenzie was an EFL teacher in Syria for several years) combined with philosophical quips, idioms, and e-text shorthand, as here:

By the milk of human kindness plus or minus what we are capable of making. One pleasure of being we is uttering it, my job is just to fix the grammar, this may hurt a little, but it is not in our best interests to rush me, thanks.

The “thanks” becomes a refrain in this series, a single word that points to communication at its most banal. MacKenzie’s language insists on the place of banality in epic human suffering. Ever faithful to perception, which can leap in one moment from deep awareness of another’s pain to passing amusement at a friend’s Twitter feed, to zoned-out half-attention to work emails. This is the world we live in. Similarly, in “Small White Bed,” the verbal gesture “No you shut up” comes in repeatedly, and this normally light-hearted negation takes on a whole new meaning as she visually and linguistically calls up associations of censorship, both voluntary and forced. In the same sequence, crossouts accomplish a more personal interpretation of this theme:

I

loveleave Manchev yelling

affection in his language

[…]

Seized with a fierce unreasonable love”

Here the speaker recoils from the ramifications of such “unreasonable” love, but leaves evidence of it in its canceled form; elsewhere we find moments of love and beauty that are fully present and generously lyrical, and herein lies the other side of being other (and being sentient). In “The Dream of the Fountain,” language becomes useless altogether and so another sense takes over:

yet I can’t feel my way forward with language

[…]

yet let what is unknown elate me

[… ]

something hitherto unknown now pleasing

I would be remiss not to talk about the feminist underpinnings of the book, which are powerful and significant. In a disarmingly understated moment near the beginning of the book, MacKenzie writes “That’s just my personal opinion / I believe every space has a gender.” Her poems are always female just as they are always Western, and often enraged at the compounded violence against women in both privileged and oppressed sectors of society. If she can’t escape her Western eyes, she also can’t escape her woman’s body. Again from “Small White Bed,” we see this feminist lens turned onto her own position as writer/poet:

& what do you know

about immensities? & is it true that becauseof our emotional natures women cannot write

anything truly grand? It is another whiteimmensity…

And drifting from a gendered to a broader question of the ‘effectiveness’ of poetry:

[That all good poetry is the poetry of exile]

is bullshit. I belong to my body & try

desperately & stubbornly to unknow it

These lines provide an important link, without which (these and a few others) the book could be at risk of imploding around its accountability conundrum. But no. Here she is pointing to her body—the fact that her position is inherently flawed/privileged, but also the ways that it is suppressed/oppressed, as well as the ways that it simply feels and is. Either way, she yearns to be

outside of it. Either way, how can we move past it? she’s asking. We start by being fully in it. The subjective and its base, the sensory, are both a trap and a stage, but the only stance from which to begin.

This book for me was like a tiny re-education center. It’s gaping and demanding—a rigorous and essential lesson. After reading it, you may feel that you’ve been schooled—and touched—in the realest, most forgiving ways that poetry makes possible.

Fence Books, 2014: $15.95

Jennifer Fossenbell lives in Minneapolis, where she writes poems, tends her offspring, and teaches writing studies at the University of Minnesota.

Chris Sylvester’s Still Life With The Pokemon

STILL LIFE WITH THE POKÉMON YELLOW VERSION TEXT DUMP IN 30 PT. MONACO FONT JUSTIFIED TO MARGIN DISTRIBUTED AS A PDF OR A BOOK CONVERTED FROM A MICROSOFT WORD DOCUMENT BY CHRIS SYLVESTER 2012/2013

1. This 691-page book is aptly described on Lulu.com as “A BOOK ABOUT A GAME CALLED POKÉMON YELLOW THAT IS A BOOK CONTAINING ALL THE TEXT FROM A GAME CALLED POKÉMON YELLOW.” Between this and the title, I find myself in a world of stupid, convoluted repetition before even opening the free pdf. Already I’m cocking my head wft?

2. Previous reviews this month have looked at other works from Troll Thread (see 1/2, 1/7, and 1/13), the collective press project run by Chris Sylvester and three compatriots. CA Conrad’s video interview with the Troll Thread crew provides a useful platform for tackling Sylvester’s POKÉMON, a book that falls under the very shady blanket of conceptualism that the four poets attempt to snap and rassle to the ground. Divya Victor talks about the pressure on poets to “continuously invent what does not exist rather than consider what does exist in discourse at all times,” a pressure that must be prodded through “devotional” textual practices revolving around trolling, bagging and manipulating the free, digital universe.

3. Similar to what Kenneth Goldsmith famously said of some of his own books, Sylvester’s is not one that is meant to be read, at least not strictly speaking, as much as it’s meant to exist, to take up excessive space on the page and in the digital territory of BOOKS (this would be heightened in print form, of course). In its aggressive excess, it’s meant to be dealt with. The cover frames the entire work as coming to its own defense: video game writer/translator Ashugi Kamaguchi’s response serves to remind us of the book’s inherent controversy and its potential reception as representative of a whole lousy world of would-be Duchamps and bullshitters. Yawn? Maybe, I think, but there still 690 pages to contend with.

4. As the title promises, the text is nothing more or less than a total capture of language found in a Pokémon video game—starting with what seems to be game world set-up as shown through long lists of characters and creatures, weapons and superpowers, accessories, places, tradable commodities with prices in yen. Nouns and pure linguistic sound accrete rapidly into stacks of animal, mineral, vegetable; texture, color and quality. This is fun? Yes, I am having fun. I am enjoying viewing every single page, keeping zoom set at 60% so I can take in each page at a glance.

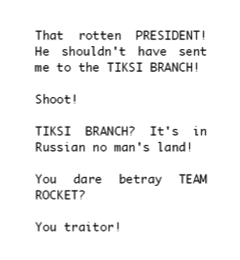

5. Eventually I pass into the action: snippets of pre-formulated conversations and disembodied commands, game-generated status reports, battle cries and interjections. The landscape becomes more unpredictable. Concrete things and invisible sequences of narrative ram up against opaque programmese and non-sequitur slapstick.

6. So apparently the player is travelling an imaginary world attempting to collect every type of Pokémon. It’s consumer training at its best. Along the way there are battles to fight, maladies to overcome, relationships to negotiate, materials to buy and paths to locate. But I’m not pushing any buttons. The book is pushing them for me. Political intrigue, infantile insult-hurling and transnational conflict are flattened, burlesqued, and painted black and white.

7. Nothing moves. Nothing is in color. Nothing makes sound. I don’t get to make any choices. I can’t control or even fully grasp the progression of the game’s narrative. This must be comparable to reading an entire comic book series as a list of speech chunks in black-and-white standard block formatting. In other words, it quickly gets boring. I start scrubbing my way through pages by the dozen, no longer able or willing to click through each one individually. This is my only agency.

8. A pheasant is shot from the sky and the pear is plucked from the tree to be painted into naturmort. But here, the dead life is language not image. Snippets of speech are disembodied and the visual narrative is stripped. The utter ridiculousness of the words are revealed out of context (to Kamaguchi’s chagrin). But so are their joyous, spring-loaded vitality and potential.

9. What draws attention to both the power and the limits of language? What removes language from action only to reveal language as its own action?

10. Here’s how a video game is like poetry: language condensation; linguistic invention; attempts at boundlessness; co-creation of experiences within a given system; reliance on and modification of conventions and clichés; a specialized fan base.

11. Here’s how a video game is not like poetry: visual animation (this is changing); who gets to set the boundaries; the number of loose parts available for construction of meaning; the size of the fan base.

12. One convention includes highly sophisticated systems (either real or made-up) of classification. On pages 612-670 (I’m back to clicking page-by-page now), I find a catalogue of dozens of Pokémon species, each with unique characteristics, abilities, and origins. Taxonomies blur and bleed when read in a continuous stream without illustration; it is difficult to tell where one type ends and a different one begins.

13. By drawing on preexisting language, Sylvester admits in Conrad’s interview, you run the risk of confusing ‘the generic’ in language practices with the apolitical. He emphasizes that “the poet doesn’t get out of what we’re all in all the time.” The goal, he says, is to figure out “how to fuck with shit without declaring oneself above the shit.” His fucking with Pokémon creates and then splashes around in a highly specific sort of shit. The dump is searching for significance where there may or may not be any but probably is. The magic (or the trick) is when I go looking for it in earnest because I start believing in earnest that it is there.

14. Reproduction in totality is a stupid exercise. Or, it is an exercise in what Sianne Ngai coins the stuplime. Sylvester’s STILL LIFE WITH THE POKÉMON is a poetry of voluminous stupidity. It is insolent and sometimes transcendent in its dumb, indefatigable self-propulsion, and it just might have special powers. It just might be a whole new type of Pokémon to be collected—a trollish one that records itself making a record of itself and then posts it on the internet for all to see.

15. Enjoy these visual aids:

http://www.shopwiki.com/l/Still-life-With-A-View

http://www.tumblr.com/tagged/pok%C3%89mon

TROLL PRESS, 2013

J. Fossenbell writes, teaches and eats gray snow in Minneapolis. Soon she’ll graduate from MFA school and become a mutha.